|

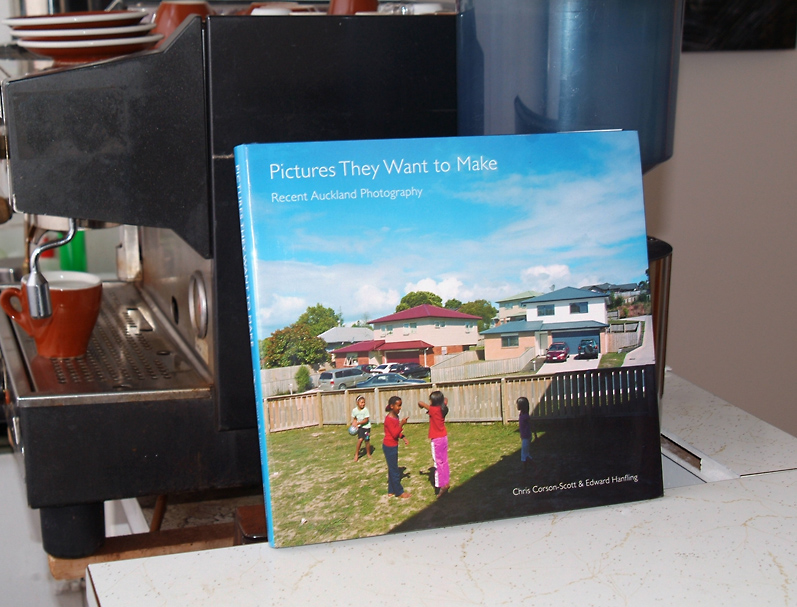

Pictures They Want to Make – Recent Auckland Photography

Chris Corson-Scott & Edward Hanfling. Published by Photoforum, Auckland, 2013 Ron Brownson’s Foreword to this lavish volume places the survey of contemporary photographers and their practices within the context of other similar projects, such as ‘The Active Eye’ (PhotoForum, 1975), ‘Views/Exposures’ (National Art Gallery, 1982) and ‘Open the Shutter: Auckland Photographers Now’ (PhotoForum, 1994. His language only lapses into artspeak for part of one paragraph, in which he seems to defend the apparent ad hoc nature of the survey: ‘[comparing to Views/Exposures] …they each coalesce current photographic practices using the trope of a visual dialectic ranging over both personal visions and public revelations. Such apparent heterogeneity was further amplified in 1994 with the idiosyncratic pluralism of [Open the Shutter]….’ Put another way, if you’re looking for some theme to connect the various bodies of work herein, or even the selection and sequencing of works within the photographers’ portfolios, forget it; none of the other surveys had a theme and neither does this one, so just relax and enjoy the photographs. The authors’ introduction sets us up well enough, explaining the term ‘picture making’, the act of which does offer a link between the practices of the chosen photographers. They excuse the looseness of the words ‘Auckland’ and ‘Recent’ in the book’s title (So why have the second part of the title?), and they exclude photographers who create scenes to photograph, focusing instead on those who photograph what already exists, but do so in more than a ‘documentary’ way. OK, so after a couple of somewhat irritated flick-throughs, I now feel more comfortable about the selection of photographers and their artworks. And I applaud the fact that this major publication is not just another unimaginative, mostly dated line-up of the usual suspects. Many of the photographers here are under-represented in high quality publications, and it is great to see their work printed so damned well. The photographers appear in alphabetical order, so we get some interesting juxtapositions. Mark Adams, an old hand and a master of photographic technique (his photographs really sing here, despite the abrupt cuts from monochrome to colour and back again) to Edith Amituanai, who has a lot of interesting stuff to say and offers a unique vision, but who still sometimes appears to struggle with composition, the workings of the camera and the vagaries of capturing light. Either it's deliberate or she doesn’t care; either way it's part of the process of the work and it references the snapshot, lending the large-format camera work an egalitarian quality, but it irritates me, and as a photographer I’m not alone with my concern about these technical shortcomings. It’s like listening to a string quartet but being prevented from enjoying the music by a smattering of bum notes from the viola player. Moving through to Fiona Amundsen’s selection, the most homogenous in the book (and not very representative of her career); she can clearly operate a camera (which, admittedly is easier when there’s no one about to bother her, in contrast to Amituanai’s photographic world), but so many German and American photographers have done this stuff quite a lot better and several decades earlier (Stephen Shore, et al). It’s a tired old riff that transplants only so well. (The same criticism could be levelled at several photographers in this volume.) It’s nice to see Harvey Benge’s photographs edited down to tight selection and reproduced rather large. His self-edited books, which he’s built his photographic career on, would mostly benefit from another set of such eyes. Benge’s images owe a lot to his strong sense of colour and design, something to his eternal globetrotting, and quite a bit to William Eggleston (who is mentioned in the introduction); but they are intriguing and they stand up well in this context. The introduction to Bruce Connew’s portfolio outlines the shifting nature of his career, and then struggles with these works for the second half of the page: “The results manifest as a kind of cutting into reality; they are precise, incisive insights; …”. I'm not so sure. These photographs seem transitional, coming after art-based projects of the recent past and perhaps indicating a return to a more direct documentary way of communicating that has been this photographer's great strength. Chris Corson-Scott’s images are the highlight for me so far. The quality! I have alas not seen the exhibition that this book accompanies (I'm only reviewing the book here), but I would really like to view these photographs full scale. They are like German objective photography but with warmth, population, and tons and tons of South Pacific light. Great photographers such as Andreas Gursky and Thomas Ruff might blanch at such contrasty conditions, but Corson-Scott has harvested the light and served it to us as a banquet. The works have a melancholy that is more subtle than Gregory Crewdson’s (currently on show at the Wellington City Gallery, and which are also large-scale prints of the highest photographic quality). Bring this show to Wellington, too, please! Ngahuia Harrison is perhaps destined to become a usual suspect in future surveys of New Zealand photography (at least if she sticks to stills and doesn’t become a film maker), but at this stage her work seems insufficiently developed for inclusion in this book. So as a writer, what do you do when there is really nothing much to say about a set of photographs? You play the Narrative card. Unfortunately this card has been so overplayed its creases and dog-eared corners make it stand out in the pack. The writers make a comparison with Crewdson, and I would suggest Ross T. Smith’s Hokianga photographs (Auckland Art Gallery, 1997) are a closer parallel. Ngahuia Harrison is fresh out of photography school. Her photograph ‘Dunedin, 2011’ is the most puzzling in the book. It is an out-of-focus, half-in-half image of some rocks and some grey water. It lacks aesthetic appeal and I’m still groping for the narrative beneath its murk. Harrison’s is one of the portfolios I will no doubt continue to return to in this book, not because I particularly like it but because I am both intrigued and challenged by it. Derek Henderson’s section comprises several pages lifted from his high-quality book ‘The Terrible Boredom of Paradise’ lapped in between some compelling portraits and landscapes taken a few years later. It is one of several portfolios in this book where works are mingled in this way, and I find it odd. Why not just run the ‘Boredom’ images, then the later works? If it’s good enough to sequence the photographers alphabetically, why not also sequence the works chronologically or thematically? Books encourage viewing images sequentially, so why unsettle the viewer with this unsympathetic sequencing that does nothing for the reading of the pictures? Also jarring, and the only miss-step in the design of the book, is the pp118/119 spread, where the image ‘Port Waikato, 2008’ crosses the gutter by a couple of centimetres. Why not just make the picture a bit smaller? This design glitch is repeated on pp170/171,and elsewhere, in varying proportions. Otherwise, the book design is immaculate, and Chinese company Everbest have done an excellent job printing and binding it. Across the single-page introductions to the portfolios, the authors have managed to cover a range of photographic topics, and the topic of digital manipulation arises in the Ian McDonald intro. It discusses the practice of compositing digital images to make a larger and more detailed picture. It is a mean to an end, and, as I’m told by someone who has seen the exhibition images, the results are highly successful. They look pretty good in the book, but in this case as with other photographers’ works, scale can only be indicated in note form. You couldn't accuse any of the included photographers of making ‘art about art' (which is, as we know, a completely pointless activity). All of them are concerned with the real world; and as with the environmentalist concerns of McDonald, Haruhiko Sameshima's photographic practice is both highly refined and socially engaged. We see a semi-outsider’s observations of our society and the values it has been built on. (Sameshima came to this country from Japan as a teenager in the early 70s.) The image of cattle crowded and quietly suffering in a truck during a ferry trip, in ‘Cook Strait Crossing, 2008’ is one example, the sweep of mountains near Queenstown with the pop-up suburb arrayed in the fore- and middle-ground is another (‘Lake Hayes Estate, 2008’). Geoffrey H. Short has taken up the reins of PhotoForum, but has huge shoes to fill—those of John B. Turner. (Two clichés in that sentence.) It’s good to see his work in this book, but the question of sequencing again rears its head. Why go Kiwi Bacon, Explosion, Explosion, Explosion, Kiwi Bacon, Kiwi Bacon, Explosion? There is no similarity between these two series, so why not just separate them? The last Explosion, though, segues by shape and texture into the first Talia Smith photo, which is a picture of a bush. This is New Topographic photography relocated to New Zealand, albeit a few decades late and lacking the American movement’s dry and minimal charm. I like her phrase, ‘areas of non-place’. And the authors say, ‘Out of this unprepossessing material, Smith makes pictures that are personal and have the capacity to surprise.’ I am surprised that the photo on pp.170/171 (another 2cm gutter-breacher) seems to be out of focus—a bit of a no-no in this field of photography, but not the only sinner of its type in the book. I guess it’s important that this concern for land use and change continues to be examined by artists, because it remains an environmental issue. But with picture-making, isn’t it important to engage, rather than repel, so that the viewer is drawn in and the concerns of the photographer are more likely to be regarded? Maybe I’m showing my Old School prejudices here, but it bothers me that recent graduates and current students in tertiary level photography programmes and art schools seem to get away with not achieving a sufficient level the craft of their chosen disciplines. In fact, achieving a high level of craft seems almost to be discouraged. Or is that being too cynical? Having spent four of my five years of tertiary education specialising in photography, having taught photography and having run a photography gallery for nearly fifteen years, I well understand that not every photo has to be pin sharp, and not every exhibition or body of images has to be the final word or the pinnacle of achievement in its sphere. I know that learning how to express concerns and passions effectively through photography is a lifetime journey. And I appreciate that not everything in this book is perfect, and it does not have to be; it is a valuable record of where a loosely-connected selection of photographers are at, and what they have been working on over the last few years, or couple of decades in some cases. To conclude, here’s another quote from Ron Brownson’s Foreword. ‘Simply put—there is more in these images than any glance can or will ever recognise. These are all loaded images demanding to be stared at, to be scanned over with a gazing intensity. They are, I sense, the equivalent of a slow-burn—images that want to be savoured with a committed looking. In many ways, they reach me as antidotes to the surfeit of photographs in our lives.’ Amen to that, brother. May we all slow down and digest fine art photographs thoroughly, as intended and hoped for by their makers. This book is not a thing to pick up and flick through. It’s a sit down, get comfy, look-at-real-slow kind of book. And it’s a come-back-to book; it is to savour, puzzle over, pick holes in, get lost in, fume about or rave about, or all of the above. Go on, buy the thing! Or it might not be too late to join PhotoForum and receive a copy in return for your subscription, if you ask them nicely. www.photoforum-nz.org Note: as a gallery owner, it is not really my place to be reviewing the work of other photographers, but I do so because there is simply not enough writing being done about New Zealand photography. I wonder what all the hundreds of graduates of tertiary photography programmes are doing. Most of them will be better placed and better equipped for reviewing than me. There are no photographers in this reviewed volume that have any connection with Photospace Gallery, and I have not published any competing volume, otherwise I wouldn't be writing the review. But the invitation is out to anyone wishing to review exhibitions held at Photospace Gallery. Don't worry, I won't get offended and hold a grudge. For long, anyway. Links:

2 Comments

James Gilberd (author)

5/8/2013 05:55:35 am

5/8/13 - Art NZ magazine, #147 - Spring 2013 - has just come out, and includes a review of Pictures They Want to Make, written by David Eggleton. I concede he writes better than I do, and he offers alternative insight into many of the portfolios in the book. He did use the word 'trope', however.

Reply

James Gilberd (author)

5/8/2013 06:06:35 am

Also see Mary Macpherson's review:

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorPhotography Matters II Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed