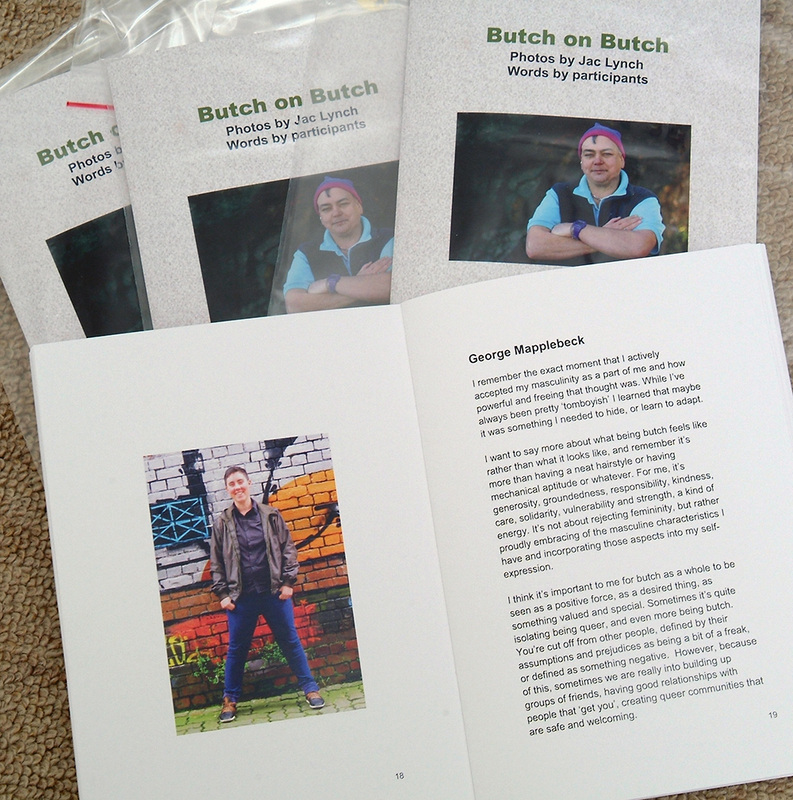

Butch on Butch - photos by Jac Lynch, Photospace Gallery 23rd Jan - 9th Feb 2015 - exhibition info18/12/2014

'Butch on Butch' is a tribute to the people among us whose masculinity defies social and gender norms. They may or may not identify as butch, but on a daily basis they are confronted with others' view of them as such. Some of the people in this series of portraits claim "Butch" proudly; some want to do so even more loudly; and for others, it's just a label. This series of photographic portraits was taken in Wellington during 2014. Jac Lynch is a butch and lives in Wellington. "Butch is an identity I embrace. I enjoy who I am. I just wish I could go to women's toilets without raising eyebrows."

This is her second solo exhibition at Photospace Gallery, following 'The Orange Room' in June-July 2013. Thank you Wellington Photographic Supplies, 11-15 Vivian St, for helping with the printing costs for this exhibition. Dominion Post article by Diana Dekker, 26th January 2015 Interview with Jac Lynch in GayNZ.com 17th January 2015

0 Comments

Photography friends have been badgering me about seeing this film since it opened, and I'd read and heard nothing but good things about it. The film reviewer in the NZ Listener, Helene Wong, gave it 5 stars (Link to review - only if you have subscriber access). I bought the book 'Vivian Maier, street photographer' (ed. John Maloof, pub. Powerhouse Books, New York, 2011) soon after it came out and have been a fan since. The photography is brilliant, no question. I applaud John Maloof for acting on his discovery and bringing this astounding, beautiful body of photographic artistry into the light. So I saw 'Finding Vivian Maier' during the week and the experience has been nagging at me since.

Street photographers tend to be gregarious only insofar as it enables them to take their shot. Maier's work, like that of Diane Arbus, Garry Winogrand, Henri Cartier Bresson and the other greats, comprises many brief engagements and interactions. The exchange lasts as long as it takes to capture the person in an indelible portrait, in which something of their inner self may be revealed along with the finest detail of their physical person, their exterior. The rest of the time, most photographers are private. Vivian Maier certainly wasn't letting anyone else in to her life when she photographed. Much of the time she would photograph as a ghost, the way most street shooters prefer to operate. Her many self portraits offer a balance to her street portraits of strangers. It's as if she's studying herself. New Zealand photographer Marti Friedlander has always taken self portraits, saying she's interested in the process of her own aging. Perhaps Maier's curiosity was similarly motivated but we'll probably never know. One thing, though, is certain; she was an intensely private person. Attention- and publicity-shy, she never sought to show her photography. Or herself. Watching John Maloof's film made me uncomfortable. While I applaud him for showing us Maier's photography, I have my doubts that his reveal of her personal life should have been made at all. I'm reminded of Richard Press's 2010 documentary film 'Bill Cunningham New York'. Cunningham was also a street photographer, apparently gregarious and engaging; but there is a moment in the film when he's asked a searching personal question and he reacts by dropping his head and clamming up. I'm fairly certain that if the film about Maier had been made when she was alive (and compos mentis), she would not have revealed any of the personal, detailed information that Maloof forensically unearthed in his obsessive gathering and study of her belongings and interviewing of people she was a nanny to. We can suppose that if she had her way, Vivian Maier might have consented to a film about her her photography, but not about her personal life. All the time, while watching the film, I felt as if I was intruding. One question; does knowing what we now know about Vivian Maier the person make viewing her photographs any more interesting? For me; no, not a jot. Actually, it slightly taints the photographs. For some photography, information about the artist affects the reading of the work (but more with conceptual work like that of Yvonne Todd. I went to her artist talk for Creamy Psychology at the City Gallery in Wellington this morning and hearing what she had to say about her photographs and some of her personal experiences and upbringing that she related indeed fed into my reading of her work.) But Maier's photographs just are: it doesn't much matter who took them. If they'd been a lost archive of an already famous photographer's work we could enjoy them just as much as images. Sure, the back story is interesting - the secretive nanny who died unknown as a photographer - but when it comes down to it, it's about the images. Do we really need to know the somewhat sordid details of the life of their author; information she would have almost certainly objected to having revealed? I also wonder if the film wouldn't have been better-made in the hands of someone other than John Maloof. Decisions about what to amplify and, more importantly, what to leave out, might have been better made by a documentary film maker with a stronger sense of ethics, resulting perhaps in a film about Maloof's discovery of Maier's photographs that we could watch without being made to feel such uneasy witnesses. |

AuthorPhotography Matters II Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed