|

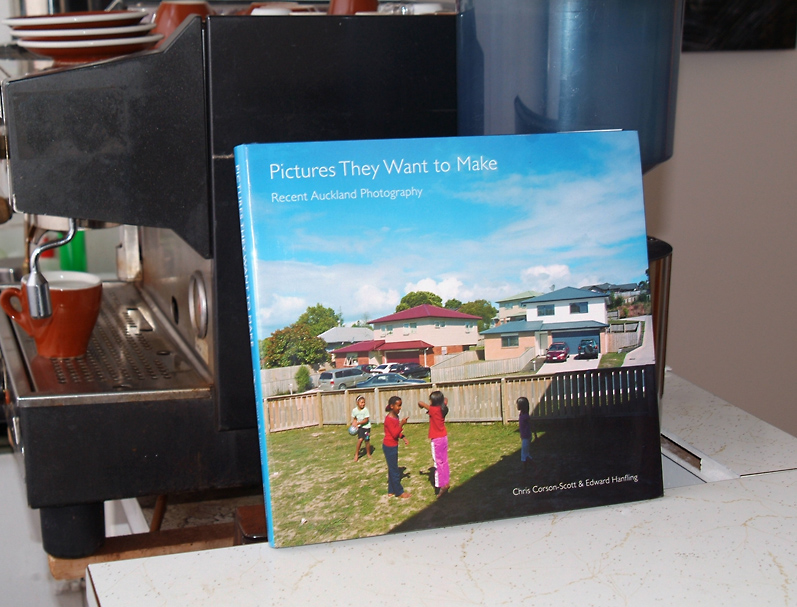

Pictures They Want to Make – Recent Auckland Photography

Chris Corson-Scott & Edward Hanfling. Published by Photoforum, Auckland, 2013 Ron Brownson’s Foreword to this lavish volume places the survey of contemporary photographers and their practices within the context of other similar projects, such as ‘The Active Eye’ (PhotoForum, 1975), ‘Views/Exposures’ (National Art Gallery, 1982) and ‘Open the Shutter: Auckland Photographers Now’ (PhotoForum, 1994. His language only lapses into artspeak for part of one paragraph, in which he seems to defend the apparent ad hoc nature of the survey: ‘[comparing to Views/Exposures] …they each coalesce current photographic practices using the trope of a visual dialectic ranging over both personal visions and public revelations. Such apparent heterogeneity was further amplified in 1994 with the idiosyncratic pluralism of [Open the Shutter]….’ Put another way, if you’re looking for some theme to connect the various bodies of work herein, or even the selection and sequencing of works within the photographers’ portfolios, forget it; none of the other surveys had a theme and neither does this one, so just relax and enjoy the photographs. The authors’ introduction sets us up well enough, explaining the term ‘picture making’, the act of which does offer a link between the practices of the chosen photographers. They excuse the looseness of the words ‘Auckland’ and ‘Recent’ in the book’s title (So why have the second part of the title?), and they exclude photographers who create scenes to photograph, focusing instead on those who photograph what already exists, but do so in more than a ‘documentary’ way. OK, so after a couple of somewhat irritated flick-throughs, I now feel more comfortable about the selection of photographers and their artworks. And I applaud the fact that this major publication is not just another unimaginative, mostly dated line-up of the usual suspects. Many of the photographers here are under-represented in high quality publications, and it is great to see their work printed so damned well. The photographers appear in alphabetical order, so we get some interesting juxtapositions. Mark Adams, an old hand and a master of photographic technique (his photographs really sing here, despite the abrupt cuts from monochrome to colour and back again) to Edith Amituanai, who has a lot of interesting stuff to say and offers a unique vision, but who still sometimes appears to struggle with composition, the workings of the camera and the vagaries of capturing light. Either it's deliberate or she doesn’t care; either way it's part of the process of the work and it references the snapshot, lending the large-format camera work an egalitarian quality, but it irritates me, and as a photographer I’m not alone with my concern about these technical shortcomings. It’s like listening to a string quartet but being prevented from enjoying the music by a smattering of bum notes from the viola player. Moving through to Fiona Amundsen’s selection, the most homogenous in the book (and not very representative of her career); she can clearly operate a camera (which, admittedly is easier when there’s no one about to bother her, in contrast to Amituanai’s photographic world), but so many German and American photographers have done this stuff quite a lot better and several decades earlier (Stephen Shore, et al). It’s a tired old riff that transplants only so well. (The same criticism could be levelled at several photographers in this volume.) It’s nice to see Harvey Benge’s photographs edited down to tight selection and reproduced rather large. His self-edited books, which he’s built his photographic career on, would mostly benefit from another set of such eyes. Benge’s images owe a lot to his strong sense of colour and design, something to his eternal globetrotting, and quite a bit to William Eggleston (who is mentioned in the introduction); but they are intriguing and they stand up well in this context. The introduction to Bruce Connew’s portfolio outlines the shifting nature of his career, and then struggles with these works for the second half of the page: “The results manifest as a kind of cutting into reality; they are precise, incisive insights; …”. I'm not so sure. These photographs seem transitional, coming after art-based projects of the recent past and perhaps indicating a return to a more direct documentary way of communicating that has been this photographer's great strength. Chris Corson-Scott’s images are the highlight for me so far. The quality! I have alas not seen the exhibition that this book accompanies (I'm only reviewing the book here), but I would really like to view these photographs full scale. They are like German objective photography but with warmth, population, and tons and tons of South Pacific light. Great photographers such as Andreas Gursky and Thomas Ruff might blanch at such contrasty conditions, but Corson-Scott has harvested the light and served it to us as a banquet. The works have a melancholy that is more subtle than Gregory Crewdson’s (currently on show at the Wellington City Gallery, and which are also large-scale prints of the highest photographic quality). Bring this show to Wellington, too, please! Ngahuia Harrison is perhaps destined to become a usual suspect in future surveys of New Zealand photography (at least if she sticks to stills and doesn’t become a film maker), but at this stage her work seems insufficiently developed for inclusion in this book. So as a writer, what do you do when there is really nothing much to say about a set of photographs? You play the Narrative card. Unfortunately this card has been so overplayed its creases and dog-eared corners make it stand out in the pack. The writers make a comparison with Crewdson, and I would suggest Ross T. Smith’s Hokianga photographs (Auckland Art Gallery, 1997) are a closer parallel. Ngahuia Harrison is fresh out of photography school. Her photograph ‘Dunedin, 2011’ is the most puzzling in the book. It is an out-of-focus, half-in-half image of some rocks and some grey water. It lacks aesthetic appeal and I’m still groping for the narrative beneath its murk. Harrison’s is one of the portfolios I will no doubt continue to return to in this book, not because I particularly like it but because I am both intrigued and challenged by it. Derek Henderson’s section comprises several pages lifted from his high-quality book ‘The Terrible Boredom of Paradise’ lapped in between some compelling portraits and landscapes taken a few years later. It is one of several portfolios in this book where works are mingled in this way, and I find it odd. Why not just run the ‘Boredom’ images, then the later works? If it’s good enough to sequence the photographers alphabetically, why not also sequence the works chronologically or thematically? Books encourage viewing images sequentially, so why unsettle the viewer with this unsympathetic sequencing that does nothing for the reading of the pictures? Also jarring, and the only miss-step in the design of the book, is the pp118/119 spread, where the image ‘Port Waikato, 2008’ crosses the gutter by a couple of centimetres. Why not just make the picture a bit smaller? This design glitch is repeated on pp170/171,and elsewhere, in varying proportions. Otherwise, the book design is immaculate, and Chinese company Everbest have done an excellent job printing and binding it. Across the single-page introductions to the portfolios, the authors have managed to cover a range of photographic topics, and the topic of digital manipulation arises in the Ian McDonald intro. It discusses the practice of compositing digital images to make a larger and more detailed picture. It is a mean to an end, and, as I’m told by someone who has seen the exhibition images, the results are highly successful. They look pretty good in the book, but in this case as with other photographers’ works, scale can only be indicated in note form. You couldn't accuse any of the included photographers of making ‘art about art' (which is, as we know, a completely pointless activity). All of them are concerned with the real world; and as with the environmentalist concerns of McDonald, Haruhiko Sameshima's photographic practice is both highly refined and socially engaged. We see a semi-outsider’s observations of our society and the values it has been built on. (Sameshima came to this country from Japan as a teenager in the early 70s.) The image of cattle crowded and quietly suffering in a truck during a ferry trip, in ‘Cook Strait Crossing, 2008’ is one example, the sweep of mountains near Queenstown with the pop-up suburb arrayed in the fore- and middle-ground is another (‘Lake Hayes Estate, 2008’). Geoffrey H. Short has taken up the reins of PhotoForum, but has huge shoes to fill—those of John B. Turner. (Two clichés in that sentence.) It’s good to see his work in this book, but the question of sequencing again rears its head. Why go Kiwi Bacon, Explosion, Explosion, Explosion, Kiwi Bacon, Kiwi Bacon, Explosion? There is no similarity between these two series, so why not just separate them? The last Explosion, though, segues by shape and texture into the first Talia Smith photo, which is a picture of a bush. This is New Topographic photography relocated to New Zealand, albeit a few decades late and lacking the American movement’s dry and minimal charm. I like her phrase, ‘areas of non-place’. And the authors say, ‘Out of this unprepossessing material, Smith makes pictures that are personal and have the capacity to surprise.’ I am surprised that the photo on pp.170/171 (another 2cm gutter-breacher) seems to be out of focus—a bit of a no-no in this field of photography, but not the only sinner of its type in the book. I guess it’s important that this concern for land use and change continues to be examined by artists, because it remains an environmental issue. But with picture-making, isn’t it important to engage, rather than repel, so that the viewer is drawn in and the concerns of the photographer are more likely to be regarded? Maybe I’m showing my Old School prejudices here, but it bothers me that recent graduates and current students in tertiary level photography programmes and art schools seem to get away with not achieving a sufficient level the craft of their chosen disciplines. In fact, achieving a high level of craft seems almost to be discouraged. Or is that being too cynical? Having spent four of my five years of tertiary education specialising in photography, having taught photography and having run a photography gallery for nearly fifteen years, I well understand that not every photo has to be pin sharp, and not every exhibition or body of images has to be the final word or the pinnacle of achievement in its sphere. I know that learning how to express concerns and passions effectively through photography is a lifetime journey. And I appreciate that not everything in this book is perfect, and it does not have to be; it is a valuable record of where a loosely-connected selection of photographers are at, and what they have been working on over the last few years, or couple of decades in some cases. To conclude, here’s another quote from Ron Brownson’s Foreword. ‘Simply put—there is more in these images than any glance can or will ever recognise. These are all loaded images demanding to be stared at, to be scanned over with a gazing intensity. They are, I sense, the equivalent of a slow-burn—images that want to be savoured with a committed looking. In many ways, they reach me as antidotes to the surfeit of photographs in our lives.’ Amen to that, brother. May we all slow down and digest fine art photographs thoroughly, as intended and hoped for by their makers. This book is not a thing to pick up and flick through. It’s a sit down, get comfy, look-at-real-slow kind of book. And it’s a come-back-to book; it is to savour, puzzle over, pick holes in, get lost in, fume about or rave about, or all of the above. Go on, buy the thing! Or it might not be too late to join PhotoForum and receive a copy in return for your subscription, if you ask them nicely. www.photoforum-nz.org Note: as a gallery owner, it is not really my place to be reviewing the work of other photographers, but I do so because there is simply not enough writing being done about New Zealand photography. I wonder what all the hundreds of graduates of tertiary photography programmes are doing. Most of them will be better placed and better equipped for reviewing than me. There are no photographers in this reviewed volume that have any connection with Photospace Gallery, and I have not published any competing volume, otherwise I wouldn't be writing the review. But the invitation is out to anyone wishing to review exhibitions held at Photospace Gallery. Don't worry, I won't get offended and hold a grudge. For long, anyway. Links:

2 Comments

The Americans’ 50th Anniversary - Steidl edition

Review originally published in www.PhotographyMatters.com, June 2008. On 15th May, 1958 Robert Frank’s book The Americans was published by Robert Delpire of Paris, after Frank was unable to find an American publisher due to the tone and content of the 83 photographs. The images, taken by the Swiss immigrant photographer on the road in the US during 1955-56, did not sit well with America’s post-WWII vision of itself as the leading nation in the world. According to the New York Times, ‘Few books in the history of photography have had as powerful an impact as The Americans.’ So says the red banner wrapped around my beautiful new Steidl edition, which arrived by post a couple of weeks ago. And I have to agree with the NYT. This is, in my opinion, the seminal photography book. Joel Sternfeld called Frank’s book, ‘a body of work that changed the course of the river of Photography in a way that it could never take the old course again.’ In New Zealand, the influence of The Americans can be seen in Gary Baigent’s The Unseen City in the 1960s and later in the photographic works of Peter Black, Lucien Rizos, Gary Blackman, John B. Turner and other sophisticated photographers. It certainly influenced my own entry to photography in the mid-80s, but I hadn’t managed to acquire a copy until now. When Lucien told me about the 50th Anniversary Steidl edition, (which he ordered on the 15th May 2008, the day it was published, because he’s a passionate Robert Frank nut) I was straight on the internet with my much-abused Visa card. As a keen book hunter, I regard buying off the internet like shooting fish in a barrel – the thrill of the hunt just isn’t there - but I’ve been hunting for a copy of this book for 25 years, so I succumbed. Robert Frank personally oversaw the production of this exquisite edition, signing off each page for the press. He went back to his own vintage prints of the images, which were then scanned in tri-tone, and it was found that images had been cropped for past editions by various publishers, so Frank revised the cropping and in many cases has included the entire image. He had input into every design aspect of this special publication, and the result is indeed a beautiful piece of book design around that still important content. Frank’s original captions and Jack Kerouac’s introduction survive intact. So while you’re faffing around on the computer, reading blogs when you should be working, why not go to Steidl’s site http://www.steidlville.com/books/695-The-Americans.html and buy the thing. It’s very good value for money, even with the postage to NZ costing more than the book. And perhaps have a look what Steidl are doing with the rest of Robert Frank’s photography books and films while you’re there. Wikipedia article: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Americans_%28photography%29 by james | 30 June, 2008 The Camera is a Small Room - a public talk by four leading NZ photographers. Review originally posted in Photographymatters.com in March, 2008 At their highest level, the photograph and the poem arrive at “that art of the marvellous” through which the compressed power of the image achieves “an endless expansion of meaning” (Fred D’Aguiar). ”This panel brings together four of New Zealand’s pre-eminent photographers, all of whom have had major survey exhibitions devoted to their work in recent years. Marti Friedlander, Anne Noble, Ans Westra and Laurence Aberhart talk about what they aspire to achieve when making images, and what purpose and power the still image retains in a world increasingly busy with moving pictures. Lawrence McDonald will talk to them about the deceptive simplicity of photography, and its role in the world of contemporary art.” Or so went the introduction, as emailed to me in the promotion. The first action of the event was something like the tactical movement of rugby lineout jumpers as the ball is thrown in, but slightly slower; it was Ans making sure she didn’t end up sitting next to Marti, which involved getting Laurence to shift seats. That intricate manoeuvre, it turned out, was the most action packed moment, as when dry-as-dust chair Lawrence McDonald introduced the discussion, things went downhill. Confusion immediately arose. The title for the talk, The Camera is a Small Room, was, we were informed, lifted from a poem by Gregory O’Brien. This ambiguous, directionless title was followed by a series of slides showing various types of camera, then some historic photographs. So, it seemed the discussion was to be about the mechanics and processes of photography. This was news to the panel and most of the audience, who thought the topic was the relationship between words and photographs. Anne Noble stuck to her original brief and presented a short talk on the latter theme. She related photography to poetry by their both being ‘condensed forms’, then explained how photographers tend to make lists and how this is like a form of poetry. She backed this idea with selected images from Peter Black’s Moving Pictures series, then her own Ruby’s Room series, giving each image a one word title; the sequence of titles was read as a list and sounded somewhat poetic. ‘Out of normal and everyday activities the world is reconfigured and given to us anew.’ I found this all quite interesting and engaging, and despite the confusion thrown in by MacDonald’s intro, very much the sort of stuff that this audience would relate to. Throwing in lovely words like ‘taxonomies’ did no harm here. Unfortunately, the next speaker didn’t seem to have any idea what the discussion was about—or care, for that matter—and so proceeded to talk about her own work in her usual manner. Marti Friedlander’s concession to the topic was to read one of her own poems and explain jokingly, ‘Now you understand why I became a photographer instead of a poet.’ One mistake she made was to say, ‘I don’t do technology’, handing over the projector remote control to the chair. Then her attempts to talk to her own slides were at the mercy of his unrehearsed pacing; he was constantly a slide or two ahead of her. The moral: if you refuse to come to grips with technology, you will end up ceding control to a third party, to your detriment. This is widely true. Laurence Aberhart, too, was in a state of confusion by the time he spoke, through no fault of his own; he said he thought the discussion topic was to do with books, as he and all of the other panelists have all authored books of photographs recently. So he talked about his book, (Aberhart, Victoria University Press, Wellington, 2007), saying that he thought most photo books, including his own, had too much writing in them, and this was mainly due to pressure from publishers. Picking up from Noble, ‘Poetry condenses, photography also condenses.’ And, ‘The image is a condensation of a much greater world.’ Stepping onto uneven ground, he said he thought a poet can’t be intuitive like a photographer. ‘You have to make leaps and stabs in an area you don’t quite understand.’ Photographers can control the accidental, whereas poets use a process of structuring and restructuring. Further, a book of poetry does not include description of what is contained in the poems, whereas photography books have pages of essays which try to explain the content of the photographs. ‘Our [photographic] publications have suffered because of the amount of words included.’ I like the way Aberhart stuck up for visual language as a thing in itself, not requiring words. This went nicely against the grain of the theme of discussion and could have provided a thread of further debate. Ans Westra was also confused about the discussion’s theme (‘The camera is a little black box- what does that mean?’), and so winged it, it appeared. She told a potentially interesting story about Hone Tuwhare, but it didn’t reach a clear conclusion. Then Question Time kicked off with a strange question from the chair, something to the effect of: ‘It has been said [by whom?] that photography as a medium is lacking in the power of narrative. What do you think of that, Marti?’ Marti: (silence…) ‘Um, sorry, can you repeat that question?’ It had me confused too. As far as I know, everyone is always trying to impose narrative readings on photographs or series of images, to the point of overkill. First I’ve heard that the medium lacks narrative ability. I wonder who said that. In response to another question, Aberhart amused the audience with the story of how people say incredibly rude and vicious things about him when he is hidden under the black cloth, operating his view camera. I asked Andrew Ross, who was sitting next to me, if he’d ever had that experience. ‘Only in Masterton,’ he replied. The audience eventually raised The Subject: digital photography verses analogue or traditional. Ans may have forgotten she was wearing a lapel mike when, in response to something Marti said, she muttered into her chest, ‘Absolute nonesense!’ The entire audience heard her clearly. Marti: ‘[Digital photography] is terrific. I’m glad it’s here. So many people enjoy it. Film photographers are so rigid…’ Ans: ‘But there are too many photographers already. It’s wasted. It’s too easy!’ I found myself agreeing with them both. Well, I reckon I got my fifteen dollars worth out of this event, but the feeling among some of the audience that I spoke to was that it wasn’t worth it. They were disappointed. One does have to question the intent of shoehorning this type of event into a writers and readers festival, but I’m not complaining. An impressive number attended, showing that there is a wide interest in New Zealand photography. The main problem was the poorly defined focus of the discussion, exacerbated by a chair who was really out of his depth in this field. I would have also liked to have seen a younger photographer on the panel, as there was the feeling that The Usual Suspects were being trotted out before us yet again. Someone like Ben Cauchi, Neil Pardington or Yvonne Todd might have livened things up a tad. 5/10. james | 18 March, 2008 The value of the image - by Deb Sidelinger

At The Camera is a Small Room last Friday, a member of the audience asked the distinguished line-up - Laurence Aberhart, Ans Westra, Anne Noble, and Marti Friedlander - what they thought of digital photography. I found myself nodding at Anne Noble’s considered response (Technology is fundamental to photography - it doesn’t matter whether the technology is mechanical or electronic - what is important is the resulting image) and cheering on Marti Friedlander in her enthusiasm (Marvelous! Fantastic! “I want to learn Photoshop… the idea of manipulating images appeals to me.”) Then, in sharp contrast, Ans Westra spoke. Digital photography, she said, made photography “too accessible”. I heard a few sharp intakes of breath at this seemingly anti-democratic remark. However, I believe that Ans Westra’s remark came not from an elitism, but from a genuine love of the craft and the image. She spoke with a sadness in her voice at the “millions of images floating around like dust particles” and “thrown into the rubbish.” One can imagine that she sees every single one of her images almost as her children… created by her, with care and love and craft. How callous this new world of image-making must seem. Images have become so easy to make that they are value-less, disposable. Take five shots in quick succession. Don’t like any of them? Delete them and start again. Take ten more. Or fifty, or a hundred. It doesn’t matter. Storage is so cheap you can take a thousand on a single flash card. Can we make these two worlds co-exist together? Can we somehow imbue digital photography with a sense of craft and digital images with a value? Can we take the best of what digital photography has to offer, and still maintain a love for the image itself? I think the answer is yes, but that’s for another post. by deb | 16 March, 2008 |

AuthorPhotography Matters II Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed