|

Here is a little interactive art installation piece. You are invited to submit anagrams of the word PHOTOSPACE via the comment section below. The work is hanging in Photospace Gallery, behind the desk in the office. Below - added on 29th October, courtesy Ed Shaw & J.Gilberd

6 Comments

This Andrew Ross exhibition, perhaps even more than his previous ones (he’s been exhibiting at Photospace Gallery at least annually since early 1999) demands close scrutiny of the photographs, and enough time in hand for the viewer to really appreciate them. Each image has its own story to tell, and it doesn’t rely on impact to deliver that story in 1.5 seconds the way a newspaper or magazine photo might. These images are quieter, less nagging, but ultimately very rewarding if you’re prepared to look into them.

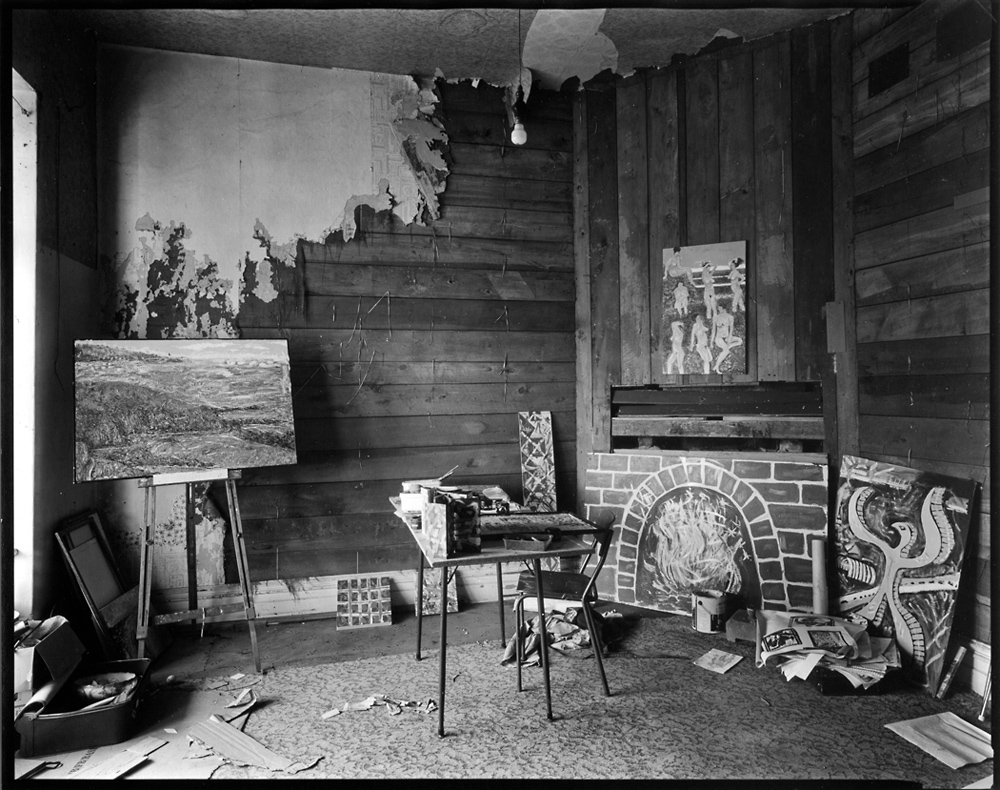

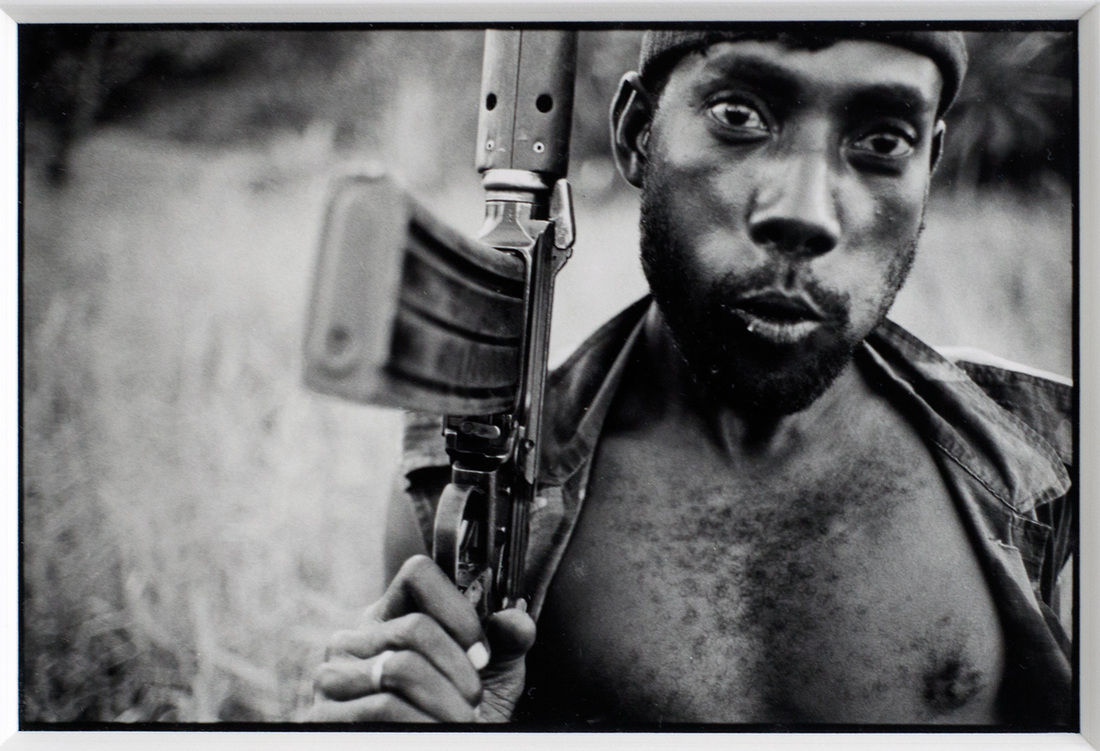

For instance, Mantel piece arrangement (a painting by Lionel Terry), 6 Elder St, Dunedin, 19/7/2010 raises the question of how the painting by the infamous murderer came to be in Dunedin at all. In 1905, Terry murdered a randomly-chosen Chinese man in Wellington’s Haining St, in order to draw attention to his own racist views on immigration. http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/3t27/terry-edward-lionel But the main story of this exhibition is of spaces in which artists of various kinds work, and how those personally-arranged environments were set up over time to operate for the individual. Some are purpose-built professional environments, such as Studio 9 at Avalon TV studios, Lower Hutt – now abandoned by Television New Zealand. Or the old Radio Active rooms in Victoria St, photographed just prior to the station’s move to new premises in Ghuznee St. As with other interiors photographed for this exhibition, sometimes the act of photography is one of the last creative acts to take place in the room, as it is soon to be abandoned, its resident/s either being forced out, moving on for other reasons, or just passing on. One front room features a coffin in the process of construction, its ever-practical Kiwi owner taking steps for his future demise. And what exactly is in the hundred-plus boxes marked “Philips Telecommunications” stacked in the back room of a defunct church in Newtown? Then there is the letter box at the Rita Angus Cottage, which was hand-painted for Rita by fellow artist Tony Fomison. Strangely, there is a ghostly swirl emanating from the letter box, going out to the right. Ross has no idea how this blurred image came to be in the photograph, and he’s generally very attentive to these matters. Could it be the spiritual presence of Angus or Fomison finding its way into the photographic image? Each photograph is lovingly made, taking around a day or two of the photographer’s time; to plan things, take the photograph, hand-develop the 8”x10” sheet film negative, make a contact print and then apply the selenium and gold toning processes. Andrew Ross, typically practical, also made his own picture frames from scratch. Studios and other interiors – photographs by Andrew Ross – shows at Photospace Gallery, 1st floor, 37 Courtenay Place, Wellington, from the 4th to the 26th of October, 2013. This photograph, taken by Bryn Evans in 1997, of a Bougainville Revolutionary Army soldier returning from a patrol, has been hanging on my wall at home since his exhibition Taim Bilong Bik Pela Pait (A time when people fought) at Photospace Gallery in 2000. Having just seen the movie Mr Pip (directed by Andrew Adamson, screenplay by Adamson, based on the novel by Lloyd Jones), the image once again called to me.

I acquired the photograph almost in response to a kind of challenge: a gallery visitor had commented, "I really like that photo but I couldn't have it on the wall, it's just too intense." This is one problem with showing documentary or photojournalistic images in a gallery; they are kinda hard to sell (but that's never been a major concern at Photospace). Another problem is the photos were originally taken not with the intention of exhibition, but for magazine publication. (The international market for magazine photo stories has declined substantially, even from what it was in the late 20th century.) So when exhibiting what are essentially press photos, how much caption information, if any, should be provided? Should the image be able to stand on its own, sans caption? Can an individual image speak for itself, without the support of its neighbours? Is that even important? I think this is one image, at least, that is capable of standing alone and speaking for itself. It is visually strong, engaging, and it speaks of armed conflict in the wider sense as well. Bryn Evans travelled to Bougainville in 1997, at the peak time of the island's struggle for independence from Papua New Guinea. He was transported from PNG to Bougainville in a small boat under cover of darkness, and even then the boat was shot at. He was the only foreign photographer on the island at the time, and it was a dangerous place for everyone, local or foreign. 20,000-30,000 people were killed in the fighting, I understand. The conflict was not widely or well covered by western media. The Wikipedia info on the Bougainville conflict is scant:

OK, that was the easy bit. Now here comes the tricky bit. After writing this far, I left Photospace for the Geoffrey Batchen lecture at the Wellington City Gallery (but via a wine tasting of the magnificent Elder Pinot). This repeat of the the 2013 Peter Turner Memorial Lecture (the first one suffered a disruption by Wellington's August 16 earthquake) got me a-thinkin'. The photo-historian's lecture discussed the present proliferation and dissemination of digital images and some artists' responses to those things, and others' art-about-photography works using photographic materials, digitisations of historic photos, etc - images and photo-objects made without cameras. While somewhat interesting, the lecture slides showed images not of any objective reality, any recording of experience, or of something that once was; but almost the complete opposite. Personally, I find photography (or non-photography) about photography about as interesting as novels in which the main character is a writer. Some of the authors write what they know but haven't been out of school long enough to know or experience anything. Bryn Evans' photograph is very much what the Batchen lecture was not about, or perhaps what is now to be considered quaint but no longer interesting; that which did once exist and was witnessed and photographed - in this case an individual human being engaged in armed struggle in a place exotic to us. This armed man walked out of the sweating jungle some time in 1997 and into the close proximity of Bryn Evans from Wellington, New Zealand, who took his photograph with a Nikon camera and a length of 35mm Kodak Tri-X black and white film. Now a silver-gelatine (darkroom-made) print of that photo sits within a frame in a house in the genteel suburb of Khandallah. (Actually, it's in the gallery for a spell.) The Bougainville photo was taken at the end of the 20th century, and perhaps it and its ilk are doomed to remain there. The 21st century doesn't care about stuff like that. It's neither intellectually stimulating enough nor entertaining enough; it just doesn't belong here, now. And even though some good people cared enough to make a feature film about the Bougainville struggle (Mr Pip), my presence in Wednesday night's audience lowered its average age, and I'm fifty. There was a noticeable absence of popcorn. But do come to the Andrew Ross exhibition at Photospace, opening tonight (October 4th, 5pm) where you can see more photos just as alien to the 21st century, but taken from firmly within it, and with great care, by an actual photographer - a very good one - who is intensely interested in the real world and the people and things that are in it. |

AuthorPhotography Matters II Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed